We have heard so much about the working-class U.S. Olympic rowing team from the University of Washington—the “boys in the boat”—that defeated Hitler’s finest in 1936. We know about its important connection to George Pocock who coached rower Joe Rantz and built the team’s racing boats. But far less known is the history of the girls in the boat, the women rowers who were waging a battle for acceptance and recognition starting at the turn of the century, a battle that also has important roots at the University of Washington and a key link to George Pocock.

Women Rowers at the UW

In the early twentieth century, the University of Washington required all students to take at least two years of a sport or gymnasium classes. Women could choose among the sports of basketball, handball, tennis, field hockey, and rowing. Starting in 1903, ten women chose rowing.

Despite this promising start, the situation for women took a bad turn in 1908 when the university cut short the future of the women’s rowing program. Even though 51 freshmen signed up for the sport, the administration decided that only current team members could continue. One reason for the decision was that the rowing program happened at the far reaches of campus, which were still wild and unurbanized, and there was therefore some concern about adequate supervision of athletes. Hiram Conibear, who in 1906 started coaching men’s rowing at UW and recruiting women to join the sport, nevertheless continued working with some female rowers on the sly, and the following year he hosted a regatta that featured women’s crew racing over 600 yards.

The next year, the Gymnasium Director and Physical Instructor of Women banned women from racing, although she did permit women to participate in form competitions in which they were given points for different elements of good racing form. But then in the fall, upon her recommendation, the administration cancelled women’s rowing altogether on the premise that rowing was too strenuous for women.

Undeterred, the women organized their own rowing club and began training twice a week.

After all the setbacks for the women’s sport, Conibear set about moving the rowers from the edges of campus to a building more centrally located. This helped prompt the administration in 1912 to reverse its decision about women rowing. However, the women had to follow certain requirements: They were still not allowed to race, they were required to change clothes at the gymnasium, not the boathouse, and they had to use rowing barges instead of shells because barges were less likely to capsize.

Lucy Pocock

The same year that UW women were allowed back into the rowing program, Aaron Pocock, who was an English master boatbuilder, relocated with his sons Dick and George (his wife had died) to the University of Washington to build boats for the school and other customers. Meanwhile, his eldest daughter Lucy, who had become family caretaker after her mother died, was making a name for herself in England as a rower. She had learned to row in Eton on a barge four with her father, her older sister Julia, and her brothers—and her younger sister as cox—racing river steamers.

Lucy, who was 6 feet tall, began competing in mixed double sculls events in 1906. She and her teammate H.N. “Blackie” Wakefield and coxswain Miss S. Goertz started winning at National Amateur Rowing Association (NARA) regattas, which were open to tradesman and artisans. In 1906 and 1907 they won the Henley Town and Visitors’ Regatta, and in 1906 they won the Newman Challenge Cup for the Championship of the Thames at the Teddington Reach Regatta.

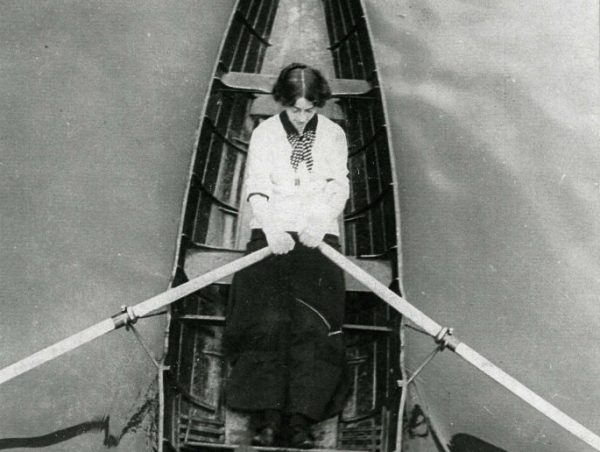

In 1912, The Daily Mirror held “a Women’s Championship of the Thames.” This was to be a revival of an 1833 Thames race featuring the wives and daughters of fishermen. The women were to row half-outrigger skiffs 1,000 yards. After five heats, 12 women including Lucy, who was 25 at the time, and her 17-year-old sister Kath, qualified for semifinals. Lucy, in a full corset and ankle-length skirt, won hers, advancing to the final before an audience of more than 25,000 people.

After a slow start in the final, Lucy took the lead over her biggest competitor, A. Brady, halfway through the race. Brady caught a crab with only 300 yards to go, and Lucy finished first by less than half a boat length. She immediately collapsed, and Brady rushed to revive her. The Daily Mirror held a rematch between the two women, and Lucy won again more decidedly, and this time Brady fainted.

With the money she won from the races, Lucy (and her sister Kath) joined her father and brothers in the United States, taking on a job as the cook for the men’s rowing team at the UW. In the fall of 1913 she was hired to coach the UW women’s crew.

The next year, 75 women signed up to row at the UW. More than 200 spectators attended their co-ed, no-racing, form-only regatta. The next year, 150 women signed up, making rowing the most popular women’s sport at the UW.

Many years later, Stan Pocock—George’s son, Lucy’s nephew, and the man for whom the BIR boathouse is named—built a lightweight women’s coxed four and named it the Lucy Pocock Stilwell after his Aunt Lucy.

Sources:

“Early Women’s Rowing on the American Frontier,” Presentation by Peter Mallory at the Annual Rowing History Symposium, Henley, 2015. http://lucypocock.com/2015_Rowing_History_Symposium_-_Peter_Mallory_Presentation.html

“Lisa Taylor: Lucy Pocock Stillwell – A Woman in a Waterman’s World?” on Hear the Boat Sing website. Abridged version of a talk given by Lisa Taylor at the River & Rowing Museum, Henley on Thames, on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2018. https://heartheboatsing.com/2018/03/16/lisa-taylor-lucy-pocock-stillwell-a-woman-in-a-watermans-world/

“Lucy Pocock Stilwell” on Rat Island Rowing & Sculling Club website. http://ratislandrowing.com/events/the-lucy-pocock-stillwell/

“Lucy Pocock and Women’s Rowing” on The American Experience website. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/boys36-lucypocock/

Featured photo shows Lucy Pocock with her cox in the Thames race.